European Memories

of the Gulag

Renvoi à divers approfondissements (textes, etc.)

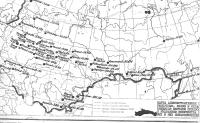

The territories of resettlement

The special resettlements were scattered across the Soviet Union. But they were mainly located in settlement regions where migrants would not go voluntarily, because they were remote and the environment was hostile.

The geography of the resettlement destinations was similar to, but did not coincide with, the geography of the camps. The special settlements were mainly in northern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, western Siberia, near Lake Baikal and an area north-east of Moscow. The camps were rather in particularly inhospitable areas, such as the Great North (Vorkuta, Inta and other camps) and the harsher parts of Siberia (Kolyma, etc.). They were often located in mining areas or beside major railway and factory construction sites. The special resettlers were sent rather to rural, arable areas or logging areas. However, there were no strict rules and the two types of deportee might be found together on working sites. But there were no special settlements west of a line from Leningrad to Moscow, where there were many camps because of a shortage of labour.

The resettlers were not kept behind barbed wire. The point was to send them to places where natural remoteness operated as a perimeter wall. These places were transformed by the resettlers, new villages were built and others that were losing their local inhabitants were rescued from disappearance. The fate of the resettlers varied over time and by place of origin. Many Lithuanians and western Ukrainians were taken to Siberia, particularly the regions of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk and Novosibirsk, while the Germans went more to Central Asia.

Ironically, these places of exile allowed national communities to form bonds of solidarity, although this was made more difficult by the ban on leaving the village and the dispersal of the settlements, adding to the deportees’ uprooting from their homes. Gradually they took ownership of their places of deportation, which became real places with an identity.

These areas emptied after Stalin’s death and even more after 1956, when the deportees were allowed to return to their homelands. Families were often scattered across the entire Soviet Union; during the 1941, 1944 and 1949 deportations from the annexed territories, many fathers were sent to camps and their wives to resettlement villages.

All this vast territory was held together by the few letters sent between home lands, where some of the deportees’ families still lived, the camps the fathers were sent to and the resettlement villages. There was a right to correspond, although it was severely restricted (one letter a month) and everyone knew that these letters were opened and read by the police.

The fathers and adult sons who survived the extremely harsh conditions in the camps went looking for their families. Some had managed to maintain a link while they were in the camp, and others spent weeks after being set free to find where they lived.

Alain Blum et Jurgita Mačiulité

The Cedar Elfin (Varlam Chalamov)

Varlam Shalamov, The Kolyma Tales, “The Cedar Elfin” http://www.paulerichardson.com; First published in Russian: Стланик. Колымские рассказы. 1960, Translation by Paul E. Richardson

In the Far North, on the boundary between taiga and tundra, among the dwarf birch and the low-growing rowan bushes—with their unexpectedly large, juicy, bright-yellow berries—and among the 600-year-old larch, which mature only after 300 years, there lives a very special tree: the cedar elfin. A distant relative of the cedar, it is a coniferous evergreen shrub with a trunk two to three meters high and thicker than a man’s arm. It is hardy and grows along mountainsides by clinging to the soil in cracks between rocks. Like all northern trees, it is brave and obstinate. And uncommonly sensitive.

It is late fall, almost winter, and snow is long overdue. For several days now, low blue clouds the colour of bruises have lurked at the edge of the white sky. And today, since morning, the penetrating fall wind has gone threateningly quiet. Does it smell of snow? No. Snow is not coming. The cedar elfin has not lain down yet. One day passes into the next and still no snow. The clouds roam somewhere behind the hills and a small pale sun enters the wide sky, entirely in keeping with autumn...

And then the cedar elfin bends. It bends lower and lower, as if under an immeasurable, ever-increasing weight. It scratches the rock with its tip and flattens itself to the earth, extending its emerald boughs. It spreads out, resembling an octopus dressed in green quills. Lying thus, it waits a day or two. Then snow spills from the white sky like powder, and the cedar elfin plunges like a bear into its wintry sleep. Huge snowy blisters swell on the white mountain slopes—these are the prostrate cedar elfin bushes, wintering over.

And toward the end of winter, when a three-meter thick layer of snow still covers the earth, when blizzards pound dense snows into the valleys, snows that only steel can penetrate, people vainly look for signs of spring in nature, even though the calendar says spring should already have arrived. But the day still feels like winter—the air is thin and dry, no different from January. Fortunately, a human’s senses are too crude, his perceptions too simplistic. In fact, he has but a few types of feelings, five in all, and that is insufficient for prophecy and divination.

Nature’s senses are more refined. We have proof of this. Remember the salmon, which will only lay its eggs in the exact river from whence it was born and grew into an adult? Or how about the mysterious routes of avian migrations? And we know plenty about barometric plants and flowers. And so, amidst the endless snowy whiteness, amidst the hopelessness, there suddenly sprouts the cedar elfin. It shakes off the snow, straightens itself up to its full height, and raises its green, icy, reddish trunk to the sky. It hears a call of spring inaudible to us and, believing it, stands erect before any others in the North. Winter has ended.

There is something else: campfires. The cedar elfin is too trusting. It so dislikes the winter that it is willing to believe in the warmth of the campfire. If, in the winter, you build a fire near a bent cedar elfin, doubled over for the winter, the cedar elfin will stand up. When the fire goes out, the disillusioned cedar, weeping from shame, will again bend and lie down whence it came. And be covered with snow.

No, it does not only foretell the weather. The cedar elfin is the tree of hope, the only evergreen in the Far North. Amid the blinding white snows, its dull green coniferous branches speak of the South, of warmth, of life. In the summer, it is modest and inconspicuous—everything around it is rushing to blossom, seeking to thrive in the short northern summer. The flowers of spring, summer and fall overtake one another in an impetuous, wild blooming. But fall is near, and already the thin yellow pine needles are falling, the deciduous trees are becoming naked, the straw-coloured grass is changing colour and drying out, the forest is emptying, and in the distance one can see how, amid the pale yellow grasses and the grey moss of the forest, there burns the massive green torches of the cedar elfins.

I have always found the cedar elfin to be the most poetic of Russian trees, better than the glorified weeping willow, the sycamore or the cypress. And wood from the cedar elfin burns hotter.

A world of women

Many witnesses remember arriving in huts in Siberia where there were only women and their children. This world of women recurs in their recollections, and often the only male present was the commandant who came once a month to check on the various families in restricted residence in a village. The men, the fathers, were in camps, from which some would return and others didn’t.

Some deportation orders specifically included “instructions for separating the deportee’s family from its head”. Men were considered more dangerous than women and generally segregation in the Gulag was strict.

The purges also hit men harder. Before the war, over 90% of the camp population were men. The figure was still over 80% after the war, although there were some women’s camps, such as the notorious ALZHIR in Kazakhstan. A number of pre-war instructions were aimed explicitly at the wives of deportees, of enemies of the motherland. They stress the strict segregation involved in the purges, not only in practice but also in the thinking of the authorities.

However, the female predominance in resettlement also reflected the high proportion of women in the Soviet Union after the Second World War. The USSR of the “second Stalinism” of the post-war years was a world with a considerable excess of women, since the war cost the Soviet Union 26 million lives, mostly men. The adult cohorts who had taken part in the fighting were particularly unbalanced.

Statistics

The general statistics available on deportation and resettlement after the Second World War seem to be at odds with the testimonies we have collected. On 1 July 1952, the figures are just under 800,000 men, just over 1 million women and just under 900,000 children, or 44% men among the adults. Are the witnesses’ memories inaccurate? Are they not remembering immediate post-war Soviet society rather than the world of the resettlers? More detail is needed to support their testimonies, because a number of reasons may explain why a general census of special resettlers may not provide the same picture as our witnesses. The census figures include peasants deported between 1929 and 1932, when men were not separated from the women and children. Similarly during the Second World War, the “punished peoples” were deported as a mass, generally without separating men from women and children. The Volga Germans, Chechens, Ingush, Greeks, etc. were sent in families to the lands of Central Asia. On the other hand, in the annexed territories after the war, men who were suspected of fighting against Soviet authority were separated from their families.

Male domination

Segregation began with the arrests. It continued in various ways in deportation, where life was even more subject to the male domination that characterised post-war Soviet society. This domination involved labour specialisation, political and police domination, etc. Commandants were all men. Men did the most qualified jobs, particularly the technical work in the growing industrial sector, while women were considered as unqualified labour. Mechanisation was associated with men, while unqualified repetitive work was given to women. There was no voluntary migration of workers in the USSR along the lines seen in Western Europe, where immigrant labour was brought in from abroad to fill the lack of unqualified workers, making up the least advantaged groups in society. This did not happen in the USSR, and even in the 1970s, there was no migration from the southern Soviet republics in Central Asia, which the authorities had seen after the Second World War as a potential reservoir of labour. Women filled the gap.

Alain Blum and Emilia Koustova

The deported prisoners’ journeys

From arrest to relegation, the deported prisoners’ journeys took a surprisingly similar shape. They would be arrested in a village and often taken by cart to the nearest railway halt, where others would be waiting; nearly all the stories begin like that. The long train was made up of cattle trucks, not always with bedframes; sometimes people had to sit or lie on the floor. All ages and sexes were crammed together. And then the journey was long, very long with no place of the destination given at the start.

Arrival was sudden, unexpected. The railway halt was usually small, in the middle of nowhere, but that was not the end of the journey. Either they continued immediately by car or lorry to their final destination. Or the deportees waited for a time in huts until they were fetched.

Forty or fifty kilometres more before they arrived in the place that would be the first stage of their resettlement. During the train journey, because the line was single-track, they would wait for ages at a station to let another train through in the other direction. The train would stop at some forsaken station in Siberia and then reverse along a route that never seemed to be direct.

The men and women organised themselves, set aside a corner of the wagon as a lavatory, with a hole in the floor and a bucket. They tried to preserve some sort of privacy. Although the children were not embarrassed, they could tell the women were. The doors were kept shut; there might be a small window that let in a glimpse of the countryside. Some had brought food; others tried to get some when the train stopped. Hot water was essential, and this was given out in stations, when one of the passengers would go and fetch it, without moving too far from the train, under the watch of the escort.

The escort soldiers only appeared when the train stopped and the wagon doors opened a little. They were not particularly violent in their behaviour, but the children could hear them shoot if anyone tried to escape. Sometimes the escapees managed to disappear into the forest. No one, of course, would ever know what became of them.

During this journey into the unknown and the uncertain, landmarks like the crossing of a large river, the passage through the Ural mountains and the first sight of the taiga took on great importance. Everyone had their own idea about where they were and what the changing landscape meant. Among these similar stories, some differences do emerge. The journeys in 1941 and 1944 were clearly more painful, with ever-present hunger and exhaustion, than those in 1949, years after the war.

These stories may also be compared with the first massive deportations during the collectivisation of 1929-1930, which were often improvised. A “deportation-abandonment” (Nicolas Werth) when the resettlers were sometimes simply dumped in the countryside. What these witnesses relate was generally not so bad. The organisation was better; they were received, even in poor conditions. The instructions published by the interior ministry departments in charge of resettlement do actually correspond fairly well to what the witnesses relate now.

Alain Blum

TIMELINE (1943-1952)

1943

February: Victory at Stalingrad, one of the turning-points in the Second World War.

November: deportation to Central Asia of some 69,000 Karachai from the Caucasus. This was the first collective operation against a “punished people” accused of mass collaboration with the occupier and expelled entirely from their lands. The national autonomy these peoples had was abolished (Karachai autonomous region, Kabardino-Balkar ASSR, Chechen–Ingush ASSR, Kalmyk ASSR).

December: deportation of some 92,000 Kalmyks from the Caucasus to Central Asia.

1944

February: deportation of some 387,000 Chechens, 91,000 Ingush and 37,000 Balkars from the northern Caucasus.

November [*?*]: deportation of some 92,000 Meskhetian Turks, Kurds and Hemshils from Georgia.

May: deportation of some 187,000 Tatars, 22,000 Bulgarians and Armenians from Crimea, 40,000 Greeks from Crimea, Georgia, Armenia and the regions of Krasnodar and Rostov.

30 July: Stalin orders the disarming, arrest and deportation of the officers and men of the Polish Home Army (AK) who had taken part in Operation Burza (tempest).

December: deportation of some 110,000 German-speakers (Volksdeutsche) living in Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.

Winter 1944-June 1945

In Carpathian Ruthenia, arrests are made of members of the Agrarian Party and Hungarian Party, Russian émigrés of the 1920s, Ukrainian and Belarusian nationalists, and Czechs and Slovaks who oppose the territory’s annexation by the USSR.

Spring 1944-1951

Arrest and deportation of hundreds of thousands of real or imagined collaborators, members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), fighters in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), Belarusian partisans, real or imagined Baltic resisters taking up arms against Soviet occupation. The families of the Ukrainian and Baltic resisters the Soviets call “bandits” are deported to resettlement villages in Siberia and the Great North.

1945

January: deportation of some 70,000 Saxons and Swabians (German-speaking Romanians) from southern Transylvania (Romania) to the Donbass, a mining area in the Soviet Union and other Ukrainian industrial areas.

Spring: deportation of some 100,000 people from Slovakia; some are forcibly taken to the USSR, particularly the Donbass, to help in reconstruction; others are sentenced as “war criminals” for fighting with the Germans, Hungarians or Slovaks (Slovakia had taken advantage of Nazi Germany’s domination to declare its independence).

April: within days of the Red Army’s liberation of Czechoslovakia and until February 1948, the NKVD arrests and deports to the USSR the Russian émigrés who had fled the Bolshevik regime in the 1920s and 1930s, mainly members of the cultural and business elite (engineers, lawyers, journalists, writers, translators, officers, teachers, diplomats, business people).

From April 1945: deportation of some 800,000 forced labourers (including 500,000 Germans) from the countries occupied by the Red Army by way of war reparations.

8-9 May 1945: Germany capitulates. The Red Army occupies part of Germany and the Eastern European countries.

Spring-summer: deportation of German-speakers (Volksdeutsche) living in Lithuania.

In Central and Eastern Europe, many people who might hamper the installation of pro-Soviet regimes are arrested and deported to the USSR.

1948

May: as land is collectivised in Lithuania, the NKVD launches Operation Vesna (Russian, “spring”): 40,000 country-dwellers, including 11,000 children, are deported to villages in the Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk and Buryatia regions.

1949

March: mass deportation operation in the Baltic countries, mainly from country areas.

In Lithuania, the operation is codenamed Priboi (Russian, “coastal surf”): nearly 9,000 Lithuanian families, some 30,000 people, are deported to Siberia.

April: similar deportation operation in Moldova.

May: operation to deport Greeks from Georgia.

1951

From June 1949 to August 1952, deportations of varying size are carried out in the Baltic countries. In October 1951, a mass operation, codenamed Osen (Russian, “autumn”) occurs in Lithuania alone, targeting only those farmers who do not join the collective farms. More than 16,000 people, including 5,000 children, are deported to Krasnoyarsk region.

Naum Kleiman tells the story of his deportation (Part 3)

This is the narrative of his deportation told by Naum Kleiman during an interview held by Irina Tcherneva and Alain Blum on 25 June 2015 at the Eisenstein Centre in Moscow. There are three separate parts.

Three separate parts can be downloaded: Part I, Part II, Part III.

Naum Kleiman tells the story of his deportation (Part 2)

This is the narrative of his deportation told by Naum Kleiman during an interview held by Irina Tcherneva and Alain Blum on 25 June 2015 at the Eisenstein Centre in Moscow. There are three separate parts.

Three separate parts can be downloaded: Part I, Part II, Part III.

Naum Kleiman tells the story of his deportation (Part 1)

This is the narrative of his deportation told by Naum Kleiman during an interview held by Irina Tcherneva and Alain Blum on 25 June 2015 at the Eisenstein Centre in Moscow. There are three separate parts.

Three separate parts can be downloaded: Part I, Part II, Part III.

Anatoly Smilingis

Detailed biography of Anatoly Smilingis

Anatoly Smilingis was born on 4 October 1927 in Plungė, Lithuania. His mother was a teacher and his father a headmaster and head of a local nationalist party. After two Soviet soldiers came to serve a warrant on them, the family was deported on 14 June 1941. His father was then separated from the rest of the family. Forever.

At the age of 14, Anatoly was left with his mother and little sister Rita. After a long journey they left the train at Kotlas and continued by river barge to the Komi Republic. A lorry took them to their final destination, “Второй участок (Second section)”, a former camp turned into a “special settlement” village.

His mother found an indoor job in the public baths, while Anatoly worked in the forest as a tree marker, measuring log sizes. At the start they still had food supplies, but by the winter of 1942 things rapidly got worse and famine was widespread. New “contingents” arrived, Poles, Chinese, Iranians, with the result that Anatoly learnt Chinese before Russian. All the deportees stuck together. After his mother was arrested and sent to a camp for stealing a few oat grains, Anatoly began to swell up from hunger and nearly died. He was saved by a bucket of wild berries that someone brought him out of pity.

Barely had he recovered than he went back to work in the forest. In 1943, he moved to Sobino special settlement village, then after the war, he got a job at the Negakeros forestry enterprise [Ust-Lekchim]. He fell ill from typhus following an epidemic transmitted by new deportees from western Ukraine. Thanks to another deportee, a military surgeon Anatoly had helped before, he managed to get a job as a hospital bursar. But all he wanted to do was to return to the forest. He so loved the forest that in the early 1950s he began running excursions for children, mainly the sons of Party members. He took them on hikes to the former camps and death pits, which was forbidden at the time. Anatoly still wonders how these boys could have been entrusted to him when he was still on the register of “special settlers”.

Before he left for Kortkeros, Anatoly went with his sister to that town’s landing stage from where Polish children were sent home. She escaped and made her way back to Lithuania. For two or three years, she lived underground. Later, when the USSR was collapsing, she joined the Lithuanian independence movement, working alongside its major figures. She now lives in Lithuania.

After Stalin’s death, Anatoly exchanged letters with an uncle exiled in the United States, who sent him food parcels, all carefully searched by the NKVD. This was before his release in 1955, the year Anatoly received an official certificate from the Republic of Lithuania announcing his removal from the special registers, and a passport limited to travel within the borders of the Komi Republic. Even later, Anatoly kept putting off his departure. He loved his work; hiking with children had brought him social recognition. He did not want to leave all that for the unknown, although his sister always urged him to return to Lithuania. He did however apply for Lithuanian citizenship: he now enjoys double nationality and receives compensation benefits from Lithuania.

Anatoly now supports memory work and memory tourism, which he has most probably pioneered in this region. He has copious archives and ten years ago he started an annual commemoration on 14 June, the date of the first deportation of Lithuanians, in the former special settlement village of “Second section”, near the cross erected in memory of the deportees. Former special settlers of all origins meet each year to share this time together.

Special settler women rafting timber 1959

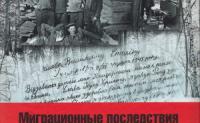

Migratory consequences of the Second World War

Three books published as part of a combined research project, supported by the FMSH and RGNF, carried out by CERCEC and the Novosibirsk State University. They are downloadable.

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2012, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Этническине депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, Volume 1, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 362 p.

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2013, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Этническине депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, Volume 2, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 236 p.

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2015, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, tome 3, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 227 p.

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2012, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Этническине депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, tome 1, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 362 p.

Table of Contents:

Часть 1. Депортационные операции и кампании | |||

| Красильников С.А. | Депортации как индикатор социальных катастроф в СССР (1930–1940-е гг.) | 7 | |

| Гуршоева Т.В. | Спецпоселенцы из Западной Украины на поселении в Иркут- ской области в 1940-е годы | 16 | |

| Башкуев В.Ю. | По обе стороны режима: наблюдательные дела как источник по истории литовской ссылки в Бурят-Монголию | 22 | |

| Аблажей Н.Н., Салахова Л.М. | 10 мая 1950 года: один день из жизни спецпо- селенцев-«оуновцев» в Иркутской области | 37 | |

| Кретинин С.В. | Массовые выселения и «изгнания» немцев из стран Цент- ральной и Восточной Европы в 1945–1949 гг.: актуальные подходы и современное состояние дискуссий | 45 | |

| Костяшов Ю.В. | Депортация немцев из Калининградской области после войны | 56 | |

| Аблажей Н.Н. | Выселение немцев из Литвы в Восточную Германию в 1951 году | 67 | |

| Носкова А.Ф. | К истории репатриации из СССР граждан II республики (1945–1946 гг.) | 73 | |

| Сарнова В.В. | Особенности статуса депортированных польских граждан и их реэвакуация из Новосибирской области в 1946 году | 85 | |

| Аблажей Н.Н. | Репатриация поляков и евреев со спецпоселения в Польскую Народную Республику в 1955 году | 98 | |

Мурашко Г.П. |

| Как и где решалась судьба венгерского меньшинства в Сло- вакии после Второй мировой войны (по материалам российских архи- вов) | 110 |

Часть 2 «Память о депортациях » | |||

Блюм А., Кустова Э. |

| Звуковые архивы. Европейская память о ГУЛАГе | 121 |

| Кравери М., Лошонци А.-М. | Траектории детства в ГУЛАГе. Поздние воспо- минания о депортации в СССР | 166 | |

| Рожанский М.Я. | Жизнеописание «везучего человека» Херша (Цви) / Гарри Цуккера | 183 | |

| Салахова Л.М., Ромадита Т.И. | История депортации: взгляд изнутри и из- вне | 199 | |

| Маркдорф Н.М. | «Власовцы» поневоле | 213 | |

| Флиге И.А. | Память о советском государственном терроре против поляков в материальном воплощении на территории России | 219 | |

| Даниэль А.Ю. | Эхо депортации: крымскотатарское движение за возвращение и предпосылки к установлению связей с правозащитным сообществом | 234 |

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2013, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, tome 2, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 235 p.

Table of Contents:

Часть 1. Депортационные операции и кампании | ||

| Носкова А.Ф. | Депортации немцев из Польши: геополитика и мораль в решениях великих держав | 3 |

| Кретинин С.В. | Массовое выселение этнических немцев с румынских территорий в 1940–1941 гг. | 24 |

| Покивайлова Т.А. | Национальные меньшинства в Румынии: проблемы депортаций и переселения в 1940-х — начале 1950-х гг. | 38 |

| Мурашко Г.П. | Проблема депортации немецкого населения из Чехословакии после Второй мировой войны: от зарождения концепции к ее реализации (по документам российских архивов) | 48 |

| Шаповал Ю.И. | Переселение польского и украинского населения в 1944–1947 гг. | 57 |

| Клейн-Гуссефф К. | Возвращение на родину: переселение польского меньшинства из Западной Украины и «репатриация» бывших польских граждан из Центральной Азии (1944–1946 гг.) | 79 |

| Аблажей Н.Н., Клейн-Гуссефф К. | 1947 год: неизвестная история советской границы | 85 |

| Слоистов С.М. | Идентичность поляков, чехов и словаков на Восточном фронте (1941–1945 гг.) | 98 |

Часть 2. Жизнь в депортации. Возвращение и память о депортации | ||

| Красильников С.А. | Адаптация спецконтингентов в Западной Сибири к послевоенным реалиям: институциональные рамки и поведенческие пратики | 112 |

| Аблажей Н.Н., Маркдорф Н.М. | Власовцы на спецпоселении в СССР | 123 |

| Башкуев В.Ю. | Сохранение этнической и религиозной идентичности литовскими спецпоселенцами в Бурят-Монголии (1948–1960 гг.) | 134 |

| Сарнова В.В. | Ссыльнопоселенцы из республик Прибалтики на территории Западной Сибири в 1941–1945 гг. | 152 |

| Мондон Э. | Судьба высланных из Западной Украины семей на примере Архангельской области (1944–1960 гг.) | 172 |

| Аблажей Н.Н., Салахова Л.М. | Режимная повседневность: особенности структуры управления и надзора в спецпоселениях | 186 |

| Рожанский М.Я. | По другую сторону депортации: семейные предания и поколенческие мифы | 197 |

| Флиге И.А. | Материализация памяти о депортациях в музеях Литвы | 211 |

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (eds), 2012, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы, tome 3, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 227 p.

Table of Contents:

| Блюм А. | Возвращение и память (вместо введения) | 3 | |

Часть 1. Возвращение и память депортации | |||

| Блюм А. | противоречивое завершение сталинизма: медленное освобождение населения, депортированного с западных территорий СССР | 12 | |

| Кустова Э. | просить, убеждать, изворачиваться: литовские спецпереселенцы ходатайствуют о возвращении на родину | 31 | |

| Сарнова В.В. | Материалы из архивно-следственных дел как источник по истории спецссылки | 54 | |

| Эли М. | Размышления о причинах сохранения системы спецпоселений в1953–1957 гг. | 65 | |

| Аблажей Н.Н. | Освобождение из ссылки: решения республиканской комиссии Армянской ССР по пересмотру дел «дашнаков», выселенных в А лтайский край | 73 | |

| Шаповал Ю.И. | Некоторые проблемы адаптации депортированных в Украинев послевоенное время | 82 | |

| Даниэль А.Ю. | память о национальных депортациях в публичном простран-стве 1950–1960-х годов | 89 | |

| Красильников С.А. | Депортанты ХХ века: крестьянская память об изгнаниии возвращении в социум | 98 | |

| Кравери М. | Еврейские судьбы в ГУЛАГе и формы мемориализации: евреи польши и стран Балтии | 112 | |

| Флиге И.А. | память о сибирских могилах | 120 | |

Часть 2. Депортационные операции | |||

| Кретинин С.В. | Интернирование и депортации немецкого национального меньшинства в польше накануне и в начале Второй мировой войны | 138 | |

| Башкуев В.Ю. | Транспортировка и расселение литовского спецконтингента вБурят-Монгольской АССР летом 1948 года | 153 | |

| Дени Ж. | Между «борьбой с бандитизмом» и раскулачиванием: операция«прибой» в Латвии (март 1949 г.) | 170 | |

| Волокитина Т.В. | Болгарские турки: проблема депортаций и переселения(конец 1940-х — начало 1950-х гг.) | 182 | |

| Мурашко Г.П., Слоистов С.М. | К вопросу о некоторых внешнеполитических факторах, определивших послевоенную политику правящих кругов чСР в отношении венгерского национального меньшинства в Словакии(1944–1949) | 196 | |

| Аблажей Н.Н. | Иностранцы, апатриды и репатрианты на спецпоселении вСССР | 213 |

Pagination

- Page 1

- Next page ››