BioGraphy

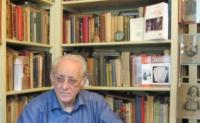

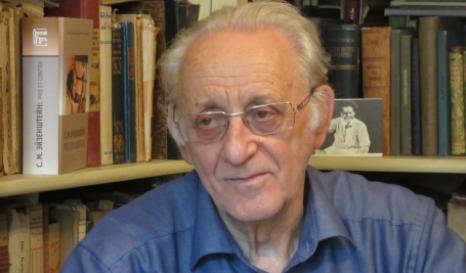

Naum KLEIMAN

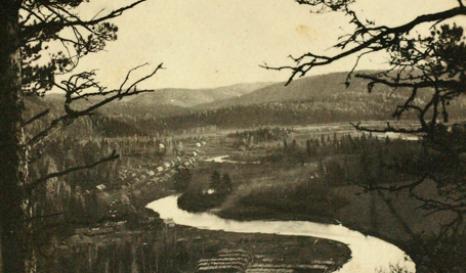

Naum Kleiman was born in Kishinev [Romania, now Chișinău, Moldova] in December 1937. His paternal grandparents lived in Bessarabia, then part of Romania. They were arrested in 1941 after the region was annexed by the USSR. His grandfather was sent to the Ivdel camp (Ivdel’lag) in the Urals, and his grandmother was deported to Central Asia. The grandfather died soon after, following a hunger strike, and the grandmother was saved by her son, who bribed local officials to have her declared dead. During the Second World War, Naum Kleiman was evacuated with his mother to the Urals, and his father joined them as a labour battalion conscript. They returned to Kishinev in 1946, but on 6 July 1949 they were all deported to the abandoned village of Yunka near Guryevsk to work in former gold mines, which produced no gold. Naum was, however, allowed to attend school in the neighbouring village of Barit, and then in the city of Guryevsk in spring 1950. Each new permission was for him a step towards freedom. He appreciates the behaviour of the local people and respects the teachers and headmasters who taught him. In 1955 he was released and was preparing to go on to higher education in Frunze (Bishkek), Kyrgyzstan, when he saw an advertisement for a course at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. For some reason he can’t now recall he applied and was accepted. So off he went to Moscow, a further step up in his quest for freedom. He graduated from the VGIK, where during the Khrushchev Thaw lecturers and students were rediscovering the hidden history of Soviet and other cinema. He became a specialist in films, especially those of Eisenstein, which enabled him to travel despite his status as a former special settler. From 1992 to 2014 he was manager of the Moscow State Central Cinema Museum and director of the Eisenstein Centre.

Alain Blum et Irina Tcherneva

The interview with Naum Kleiman was conducted by Alain Blum and Irina Tcherneva.