European Memories

of the Gulag

Renvoi à divers approfondissements (textes, etc.)

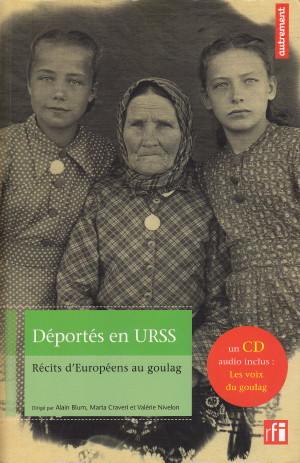

Deportees to USSR – Stories of Europeans in the Gulag

Blum Alain, Craveri Marta, Nivelon Valérie (dir.), 2012, Déportés en URSS - Récits d'Européens au Goulag [Deportees to USSR – Stories of Europeans in the Gulag], Paris (France), Autrement, 336 p.

Table of Contents (the book is in French)

| Alain Blum et Marta Craveri | Introduction | 5 | ||

| Valérie Nivelon | Voices of witnesses | 16 | ||

| Alain Blum et Marta Craveri | Deportations to the USSR: a long history | 19 | ||

| Françoise Mayer | USSR, land of promise? | 29 | ||

| Catherine Gousseff | Details and drift of memory | 48 | ||

| The environment (illustrations) | 63 | |||

| Marta Craveri | Saved by deportation | 69 | ||

| Agnieszka Niewiedzial | Fighting and resisting | 87 | ||

| Work (illustrations) | 103 | |||

| Juliette Denis | Images of childhood | 109 | ||

| Isabelle Ohayon |

| Finding a place in silence |

| 132 |

| Anne-Marie Losonczy | Surviving. A bitter school and the humour of God | 145 | ||

| Childhood (illustrations) | 167 | |||

| Mirel Banica | Hunger, an endless struggle | 175 | ||

| Malte Griesse | From Soviet special camps in Germany to the camps in the Gulag | 186 | ||

| Community and religious life (illustrations) | 207 | |||

| Alain Blum | Difficult return | 212 | ||

| Emilia Koustova | Becoming Soviet ? | 228 | ||

| Culture and leisure (illustrations) | 245 | |||

| Jurgita Mačiulytė | A peasant soul | 251 | ||

| Marc Elie | Penitential journey of an ultranationalist | 267 |

Publications

Below are selected publications, written wholly or in part on the basis of this project, published before September 2018.

Books

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain, 2013, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Этническине депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы [Migratory consequences of the Second World War. Ethnic deportations in the USSR and Eastern Europe], Vol. 2, Novosibirsk (Russia), Nauka, 236 p.

- Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain, 2012, Миграционные последствия Второй Мировой Войны: Этническине депортации в СССР и странах Восточной Европы [Migratory consequences of the Second World War. Ethnic deportations in the USSR and Eastern Europe], Vol. 1, Novosibirsk (Russie), Nauka, 362 p.

- Blum Alain, Craveri Marta, Nivelon Valérie (dir.), 2012, Déportés en URSS. Récits d’Européens au Goulag [Deportees to USSR – Stories of Europeans in the Gulag]. Paris (France), Autrement, 336 p.

- Craveri Marta and Losonczy Anne-Marie, 2017, Enfants du Goulag [Gulag Children], Paris, Belin.

Articles

- Blum Alain, 2015, « Décision politique et articulation bureaucratique: les déportés lituaniens de l'opération "Printemps" (1948) », Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, 62(4), pp. 64-88.

Blum Alain et Koustova Emilia 2018, "Negotiating lives, redefining repressive policies: managing the legacies of Stalinist deportations", Kritika. Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 19, 3, pp. 537-571.

Blum Alain et Regamey Amandine 2012, “Le héros et la martyre ou le viol efface (Lituanie, 1944-2000), Clio N°39 “Les lois genrées de la guerre”, 2014.

Craveri, Marta et Losonczy, Anne-Marie, 2012, “Trajectoires d'enfances au goulag. Mémoires tardives de la déportation en URSS”, Revue d’histoire de l’enfance « irrégulière », Le Temps de l’histoire, Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp.193-220

Koustova, Emilia, 2015, « (Un)Returned from the Gulag : Life Trajectories and Integration of Postwar Special Settlers”, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 16, 3, pp.589-620.

Koustova, Emilia, 2014, « ‘Спецконтигент’ как диаспора ? Литовские спецпереселенцы на пересечении множественных сообществ » [‘Contingent spécial’ comme diaspora ? Les déportés spéciaux lituaniens au croisement des communautés multiples], Новое Литературное Обозрение 127, 3, pp. 543-557.

Losonczy Anne Marie, 2019, «"Nos années de souffrance". Mémoire du Goulag et construction ethnique post-communiste chez les Hongrois de Transcarpathie (Ukraine)» , Revue comparative Est-Ouest,41, 1, pp. 163-190.

Ohayon Isabelle, "Ego-récits de l’intégration : deux itinéraires de déportés au Kazakhstan soviétique", Slovo, Presses de l’INALCO, 2017, Le discours autobiographique à l’épreuve des pouvoirs Europe - Russie - Eurasie, pp.239-252. 〈http://slovo.episciences.org/〉

Tcherneva Irina, « Exploring visual resources for a history of imprisonment. Photo and Film in penal spaces in the USSR (1930–1970) », The Evolution of Prisons and Penality in the Former Soviet Union, numéro spécial, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, https://journals.openedition.org/pipss/.

Books chapters

- Blum Alain, Koustova Emilia 2017, “A Soviet story – Mass deportation, isolation, return”, in Davoliūtė Violeta and Balkelis Tomas (eds), Maps of memory: trauma, identity and exile in deportation memoirs from the Baltic states, Budapest, CUP.

- Koustova, Emilia 2017, « Equalizing Misery, Diderentiating Objects: The Material World of the Stalinist Exile » in: Graham H. Roberts (éd.), Material Culture in Russia and the USSR. Things, Values, Identities, London: Bloomsburry Publishing, pp. 29-53.

- Koustova, Emilia « Труд и адаптация спецпоселенцев на примере послевоенных депортаций из Восточной Европы » [Le travail et l’adaptation dans les « villages spéciaux » : les déportations soviétiques de l’Europe orientale] in : История сталинизма. Принудительный труд в СССР. Экономика, политика, память, Moscou : Rosspen, 2013, pp. 65-77.

- Blum Alain, 2015, Противоречивое завершение сталинизма: медленное освобождение населения, депортированного с западных территорий СССР, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 12-30

- Blum Alain et Koustova Emilia, 2012, Звуковые архивы. Европейская память о ГУЛАГе, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit. 121-165

- Blum Alain, 2015 Возвращение и память (вместо введения), in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 3-11

- Craveri Marta et Losonczy, Anne-Marie, 2012, Траектории детства в ГУЛАГе. Поздние воспо- минания о депортации в СССР, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit. 166-182

- Craveri Marta, 2015, Еврейские судьбы в ГУЛАГе и формы мемориализации: евреи польши и стран Балтии, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 112-119

- Denis Juliette, 2015, Между «борьбой с бандитизмом» и раскулачиванием: операция«прибой» в Латвии (март 1949 г.), in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 170-181

- Elie Marc, 2015, Размышления о причинах сохранения системы спецпоселений в1953–1957 гг., in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 65-72

- Gousseff Catherine, 2013, Возвращение на родину: переселение польского меньшинства из Западной Украины и «репатриация» бывших польских граждан из Центральной Азии (1944–1946 гг.), in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 79

- Koustova Emilia,2015, Просить, убеждать, изворачиваться: литовские спецпереселенцы ходатайствуют о возвращении на родину, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 31-53

- Mondon Hélène, 2013, Судьба высланных из Западной Украины семей на примере Архангельской области (1944–1960 гг.), in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 172-185

- Ablazhey Natalia et Gousseff Catherine, 2013, 1947 год: неизвестная история советской границы, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 85

- Ablazhey Natalia et Salakhova Larissa, 2013, Режимная повседневность: особенности структуры управления и надзора в спецпоселениях, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 186

- Salakhova Larissa et Tatiana Romadita, 2012, История депортации: взгляд изнутри и из- вне, in Ablazhey Natalia, Blum Alain (dir.), op. cit., 199-212

Table of contents of Deportees to USSR – Stories of Europeans in the Gulag

- Alain Blum and Marta Craveri, "Introduction", 5-15

- Valérie Nivelon, "Voices of witnesses", 16-18

- Alain Blum et Marta Craveri, "Deportations to the USSR: a long history", 19-28

- Françoise Mayer, "USSR, land of promise?", 29

- Catherine Gousseff, "Details and drift of memory", 48-62

- Marta Craveri, "Saved by deportation", 69-86

- Agnieszka Niewiedzial, "Fighting and resisting", 87-102

- Juliette Denis, "Images of childhood", 109-131

- Isabelle Ohayon, "Finding a place in silence", 132-144

- Anne-Marie Losonczy, "Surviving. A bitter school and the humour of God", 145-166

- Mirel Banica, "Hunger, an endless struggle", 175-185

- Malte Griesse, "From Soviet special camps in Germany to the camps in the Gulag", 186-206

- Alain Blum, "Difficult return", 212-227

- Emilia Koustova, "Becoming Soviet?", 228-244

- Jurgita Mačiulytė, "A peasant soul", 251-266

- Marc Elie, "Penitential journey of an ultranationalist", 267-

TIMELINE

TIMELINE (1939-1941)

1939

23 August: the German-Soviet Pact, signed by Ribbentrop and Molotov, seals for a time an alliance between Germany and the Soviet Union and marks out each country’s spheres of influence in Central and Eastern Europe.

1 September: Hitler invades Poland, unleashing the Second World War in Europe.

17 September: Soviet troops enter Poland and the eastern part of the country is annexed to the Ukrainian and Belarusian SSRs.

September-October: the USSR forces the Baltic states to sign mutual assistance treaties. Wilno (now Vilnius), which had been Polish before the war, is detached from Belarus and joined to Lithuania.

November 1939-March 1940: the “Winter War” between the USSR and Finland, which stands up against the territorial demands of its powerful neighbour.

1940

In 1940 and 1941, the Soviets, who annexed eastern Poland (western Ukraine and Belarus) under the German-Soviet Pact, arrange four major waves of deportation from these regions designed to purge them of “undesirable elements”. Each deportation operation has a clear target at the outset.

February: deportation of the military settlers, osadnicy, Polish Army veterans who had fought during the First World War or in the Russian-Polish war of 1920 and had been allotted land with the strategic objective of establishing a Polish presence in the border areas.

April: deportation mostly of representatives of the former Polish law enforcement system (urban and rural policemen, prison warders, administrative staff), members of the propertied classes (landlords, self-employed craftsmen, manufacturers, shopkeepers) and relatives of those already purged.

June: deportation of refugees who fled from western Poland when it was occupied by the Germans. Staying in western Ukraine and Belarus, now in Soviet hands, they are offered citizenship. Those who refuse are deported to Siberia or the Great North. Of the 75,000 deportees, 80% are Poles of Jewish origin.

June-July: after the Fall of France, Stalin accelerates the annexation of the Baltic states into the USSR.

The Red Army enters the three countries, and emissaries are sent from Moscow to coordinate the annexation with the help of local forces. The Baltic states become Soviet Socialist Republics.

1941

June: the fourth and last operation is held not only in the former Polish eastern territories but also the three Baltic countries and Moldova (annexed in August 1940), with the aim of “cleansing” these areas, in the terms of the Soviet decrees, of anti-Soviet, criminal and “socially dangerous” elements.

In this operation, ten categories are targeted and divided between those who are to be arrested and sentenced to hard labour and those who are to be deported and put under house arrest in special settlements.

The active members of counter-revolutionary and nationalist parties, former police officers, rural policemen, prison warders, senior civil servants and former officers compromised by written evidence, land owners, industrialists and businessmen, and criminals are to be sentenced to from 5 to 8 years’ forced labour; their property is to be confiscated and once they have served their sentences they are to live in internal exile for 20 years in distant regions of the USSR. The families of people in these categories and German refugees who ought to have been repatriated to Germany but had refused the transfer – for whom there is evidence of anti-Soviet activity or suspected contacts with foreign counter-espionage – are to be deported for 20 years to special settlements and have their property confiscated.

More than 85,000 “anti-Soviet elements” are deported in this way to special settlements in Siberia and Kazakhstan, including 37,000 from eastern Poland, 23,000 from Moldova and 25,000 from the Baltic countries. Of the Baltic deportees, 12%-15% are of Jewish origin.

22 June 1941: start of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of the USSR. The four years of this “Great Patriotic War” are marked by bloody fighting, extreme living conditions and murderous occupations: more than 25 million Soviet citizens die. The western borders of the USSR are the first territories occupied by the Germans; they quickly apply their policy of exterminating the Jews.

July 1941: Sikorski-Mayski Agreement signed in London by the premier of the Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet Ambassador to the UK, following which a decree is issued on 12 August granting “amnesty” to the Poles imprisoned or deported to the USSR and the Anders Army is formed on Soviet territory.

August: deportation to Central Asia of approximately one million Germans from the Volga, Caucasus and Crimea, accused of collusion with Nazi Germany. The Volga German ASSR is abolished.

September: deportation to Kazakhstan of some 89,000 Finns from the Leningrad region.

Alain Blum et Marta Craveri

Work in deportation

Work was the centre of life in deportation. It was the whole of life in the camps. It was essential both for survival and for integration into the world where the deportees would have to live.

Work in the villages of special resettlers was different from that in the camps. It was usually rural work, fieldwork on kolkhoz and sovkhoz farms, logging. In the camps, the prisoners were used mainly in building railways and mining. The distinction between special resettlers and prisoners was not a hard and fast one. For example, there were agricultural camps, particularly in Kazakhstan. Special resettlers often worked alongside prisoners building railways or in factory work.

The deportees could survive by doing extra work personally, which enabled them to integrate into the local social fabric. In the camps, forced labour was 100% of their work. Although they were all subject to extremely hard work, the depths of violence were to be found in the camps, where working conditions, especially in winter, were at the limit of what a human being could take.

The camps formed the basis of a vast industrial sector covering the whole production process from mining in Siberia to the finished manufactured product, even including basic and applied research, in specially designed camps for purged scientists and engineers. The resettlers often worked alongside prisoners building railway lines or new cities to support the industrial development of a region.

The resettlers discovered work that was chosen for them. They were often recruited on arrival, as in a slave market, by kolkhoz chiefs. They were given the hardest work, particularly on the huge logging operations, lespromhoz, in Siberia. This was probably less of a contrast for Lithuanian or Latvian peasants, or Ukrainian farm workers, than for towndwellers who knew little of rural life. But the latter had skills that stood in for their lack of experience.

The line between free or deported workers and prisoners was not always a clear one in areas where forced labour was the rule. Often, when their sentence was over, prisoners would settle locally either voluntarily, because they had nowhere to go back to, or because they were under restricted residence with no right of return. So they would be living among their former camp mates. The special resettlers often worked alongside the locals in the same working teams and on the same conditions.

Alain Blum and Emilia Koustova

Soviet purges in eastern Poland and the Baltic countries 1939-1941

Following the pact signed by the German and Soviet foreign ministers Ribbentrop and Molotov, the Soviet Union annexed Poland’s eastern territories in September 1939 (as western Ukraine and Belarus) and the three Baltic countries in July 1940.

The political, economic and military elites of the various “nationalities” (in the Soviet sense of ethnic group: nacionalnost) living in these territories (Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians and Belarusians) were arrested and sentenced to forced labour in Soviet labour camps or deported and placed under house arrest in Siberia and Central Asia.

In eastern Poland, from 1939 to 1941, the Soviets arrested and sentenced to forced labour 107,140 persons, of whom 23,590 Jews. At the same time four major waves of resettlement were held to purge the eastern regions of “undesirable elements”. Each resettlement operation had a precise target from the outset.

The first, in February 1940, was aimed mainly at the osadnicy settlers, the Polish Army veterans who had fought during the First World War or in the Russian-Polish war of 1920 and had been allotted land with the strategic objective of establishing a Polish presence in the border areas. Among the 140,000 resettlers there were also other categories of people: farmers and employees of the former forestry administration.

Poles of Jewish origin were mainly deported during the second and third operations in April and June 1940. Whereas in April, those deported were mostly representatives of the former Polish law enforcement authorities (urban and rural policemen, prison warders, administrative staff), members of the propertied classes (landlords, self-employed craftsmen, manufacturers, shopkeepers) and relatives of those already purged, in June 1940, the category targeted was refugees, for whom the Soviets created the term “special settler-refugees” (spetspereselentsy-bezhentsy). People in this category were those who had fled from western Poland when it was occupied by the Germans and then, for fear of not being able to return to Poland, where their families still were, had refused to take Soviet citizenship and had applied to the Soviet-German population transfer commission to be allowed to return to western Poland.

Rumours of the brutality of the NKVD agents during the first deportations and the risks for those who refused passports and citizenship caused these refugees to put their names on the lists of the population transfer commission. “Some decided to cross over to the German side of the border,” writes one witness. “Admittedly, the Nazis put the Jews in ghettos, but they did not have a Siberia. Of the two evils (there were no gas chambers as yet), some Jews thought they were choosing the lesser, since they could not imagine that it would have been Siberia that was the ‘lesser evil’.”

All those who were not allowed by the Germans to return to the western part of Poland were deported by the Soviets. Of the 77,000 deportees in the third wave of June 1940, 80% were of Jewish origin.

The fourth and last operation, in June 1941, covered not only the Polish eastern territories but also the three Baltic countries and Moldavia (annexed in August 1940). The aim was to “cleanse” these territories – the word used in the Soviet decrees – of anti-Soviet, criminal and “socially dangerous” elements. In this operation, ten categories were targeted and divided between those who were to be arrested and sentenced to hard labour and those who were to be deported and put under house arrest in special settlements. The active members of counter-revolutionary and nationalist parties, former police officers, rural policemen, prison warders, senior civil servants and former officers compromised by written evidence, land owners, industrialists and businessmen, and criminals were to be sentenced to from 5 to 8 years’ forced labour; their property was to be confiscated and once they had served their sentences they were to live in internal exile for 20 years in distant regions of the USSR. The families of people in these categories and German refugees who ought to have been repatriated to Germany but had refused the transfer – for whom there was evidence of anti-Soviet activity or suspected contacts with foreign counter-espionage – were to be deported for 20 years to special settlements and have their property confiscated.

Marta Craveri

Suggest a room

To suggest a room about a witness or a topic

The virtual museum Sound Archives – European Memories of the Gulag operates on the same lines as a review: a room is considered to be like a scholarly publication and is vetted by the museum editorial committee, comprising the project team and two outside referees.

But it is a publication combining audio or video extracts of testimony, period documents, personal documents, short commentaries, more detailed texts, archive documents.

- We invite researchers who wish to submit a room (as they would submit an article) to send us their room suggestion on the form provided. It will be submitted to the museum editorial committee and two external referees. If the room is accepted, it will be published in the museum, with the names, naturally, of its author or authors.

A room must contain

1. The name of the room’s author(s) with a short biography, organisational affiliation and main publications. This information is to be entered in the “Comments” box of the suggestion form.

2. The name of the room

3. A presentation text of no more than 1,200 characters (this will appear in the left-hand column of the room)

4. A collection of media, images, texts or audio.

- Audio interview extracts or other audio media. These must be of good quality, preferably in wave, mp3 or ogg files. The sound media should not exceed 4 or 5 minutes at the most and be supplied in their original language, with preferably a written translation in English or French, or, failing that, a transcript. They should be accompanied with copyright transfer form. Details should be given in a separate file of the date of the interview, place of interview, short biography of the interviewee, names of the interviewee, interviewer and others present at the interview. It is essential to complete and enclose a personal or general authorisation to publish the interviews. We can supply the relevant form if required. All other audio documents must be described and free of copyright.

- Where appropriate, the full interview for the archives, accompanied if possible by a log of the various stages of the interview (time codes and descriptions of topics).

- Video extracts (same conditions as for audio extracts)

- Text media for the “More information” heading in the room. The text may be longer (not exceeding 30,000 character), together with an abstract.

- Archive documents to support the room, accompanied by commentaries (the archive documents must be free of copyright and supplied as images or text). The image media should be assembled in thematic slide shows. Each image must be documented: copyright, title, other details. They must be accompanied by a copyright transfer form or a document certifying that the documents are free of copyright. Each slide show (set of images) should be accompanied by a text not exceeding 1,200 characters. The image media and audio to illustrate the room should be identified.

- Preferred organisation for the room.

- A bibliography.

To comment [EN]

If you want to comment on your museum visit or a particular room, please send us your comment (in English, French, Polish or Russian)

To comment on a previous comment:

It will be posted after moderation by a member of the museum editorial committee.

Contact Form

Contact Form

The “Great Turn” in 1930

The “Great Turn” in 1930 saw the launch of forced collectivisation in the Soviet countryside with as corollary the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class”. The Politburo took only three weeks to plan the details of this unprecedented purge. Of the three targeted categories of “kulak”, the second comprised a quota of 150,000 peasants not involved in counter-revolution, but belonging to the richest group. They were to be deported in families to the most remote parts of the USSR. The purpose was both to isolate these “class enemies” far from the villages to be collectivised and to use their labour to exploit the mineral resources of inhospitable regions.

This gave the go-ahead for the Stalin era’s first mass deportation. In the winter of 1930, more than 550,000 peasants were deported in inhumane conditions. The original quotas, considerably exceeded, confirm that “dekulakisation” was unrestrained. In the major grain-growing areas (Lower and Mid-Volga, Central Black Earth Region, Ukraine and Belarus republics), expropriation turned into petty revenge and plundering. The purge affected most of the middle-income peasantry. Although they were supposed to leave with two months’ worth of provisions, warm clothes and tools, families were woken in the middle of the night, ordered to get ready in half an hour, and sent to the nearest station, where they were loaded onto goods trains for unknown destinations. These methods became a ritual during subsequent deportations.

In 1930, it was the North region that received the largest contingent of deportees: more than 230,000 were “hosted”, of whom nearly half came from Ukraine. In May 1930, this type of purge was given the name “special settlement” and its victims were called “special settlers”. A new group excluded from Soviet society was formed. This was families deported by administrative order for an indeterminate period. They were put to forced labour and had to build the “special villages” where they would be prisoners. The regional authorities were so unprepared that the deportees were dumped on wasteland in the middle of the forest. The first winter of deportation was chaotic. In the absence of coordination between central government and the remote areas, the families were poorly supplied with food, and the forestry firms that used their labour were unwilling to provide accommodation. Cold, hunger and epidemics were part of their daily lives. In the North region, one-third of the deportees had died or run away by the end of 1930. As a result, the economic value of the deportees was zero.

In spring 1931, the OGPU, considered to be more effective at “managing” prisoners, took over and organised within the Gulag a “special settlements” administration with regional centres and local komandaturas headed by “commandants”. Despite the failure of the 1930 deportation, a further wave of forced migration was begun in 1931 with the expulsion of more than 1,200,000 “dekulakised” peasants. This time, 430,000 of them were sent to the Urals. Siberia had to take more than 300,000 and Kazakhstan nearly 250,000. For the first three years of their exile, the punitive policy towards the peasants caused enormous waste and a humanitarian disaster that peaked in the 1933 famine. In all, the political police recorded for those years nearly 500,000 deaths and 670,000 escapes. This time the failure was perceived by the central authorities, who gave up their plans for a “vast” new deportation in 1933, targeting two million peasants.

From 1934, the situation improved for the deported peasants because of the “special artels” that were set up in their villages. Plots of land, cattle and seed stock enabled the families to gradually reorganise their lives. The deportees got used to the forestry and mining work they were given. In 1935, nearly 445,000 deportees were working in the agricultural sector, and 640,000 were employed by industrial firms. The most enterprising peasants managed to get promoted to positions of responsibility, which was made easier by the lack of labour in these remote regions. The demographic turning point was 1935, when births outnumbered deaths. Normalisation also began with the first moves to restore to the peasants their civic rights. However, Stalin’s announcement in January 1935 that there was to be no return sealed their fate. The “kulak operation” in July 1937 began a new wave of purges of “heads of family” in the “special villages”: more than 46,000 “former kulaks” were arrested. A year later, the first amnesties were announced, for young people to leave their assigned villages to pursue their studies or work. Normalisation was also economic: the artels became ordinary kolkhozes. In 1939, Beria even considered ending the peasants’ exile and abolishing the system of “special settlements”. The plan was scrapped because of the new waves of deportation after 1940 and the start of the war. In 1942, nearly 61,000 “labour settlers” were put into uniform, primarily young people. They were removed from the “special registers”. But vigilance was increased for the older generation, who had to wait until the post-war years to be freed from their shameful status. At the end of the 1940s began the slow process of granting amnesty to “former kulaks”, which continued until 1954.

Hélène Mondon

Other life stories

Autobiographies, biographies, romans

Bibliography, compiled by Antonio Ferrara, of books published in English, French and Italian

Autobiographies

Kostancija Bražėnienė, Just One Moment More… The story of one woman’s return from Siberian exile. The letters of Kostancija Bražėnienė written from Lithuania, East Germany and Siberia, 1944-1966, Boulder (CO) 2007

This book is made of letters written by the authoress and her son between 1944 and 1966. Authoress was deported to Siberia in March 1949 and released in 1956. Letters cover mainly the period after the release, offering useful insights in the life of former convicts. There is less about the life in deportation since the authoress was not allowed (until 1953) to write letters. NB authoress’ daughter married (without her mother’s knowledge) Lithuanian partisan leader Juozas Lukša, and that made much more difficult the authoress’ emigration.

Wojciech Jaruzelski, Les chaînes et le refuge: mémoires, Paris 1992

Author (b. 1923) was exiled to the Altaj region in 1941; in 1943 joined General Berling’s Polish Army; his mother and sister came back to Poland in 1946.

Daniel Libeskind-Sarah Crichton, Construire le futur: d'une enfance polonaise à la Freedom Tower. Paris: Albin Michel, 2005

Author’s parents Nachman (1909-2001) and Dora (d. 1981) were both imprisoned in the Gulag in 1940-1941, and met each other in Soviet Central Asia where author’s sister was born in 1943. Libeskind relates at some length about their experiences.

Moshe Prywes–Haim Chertok, Prisoner of Hope. The Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry series, 22. [Waltham, Mass.]: Brandeis University Press, 1996

Autobiography of a prominent Israeli physician, whose family inspired I. Singer’s novel The family Moskat. In April 1940 he was deported from Bialystok to the Vierchni-Tchov ITK in the Komi Republic. In 1944 he is released and moves to Kherson, in Ukraine, which he leaves in 1946 for Warsaw, then Gdansk. He then emigrates via Sweden to Paris, where he works for the JDC, and in 1951 leaves for Israel (where he helps establish medical schools at the Hebrew University and then in Beersheva).

Klemens Rudnicki, The Last of the War Horses. London: Bachman & Turner, 1974

Memoirs of a Polish general who was imprisoned in Dnipropetrovsk prison and then sent as a “free deportee” to Kirov in 1940-41, then freed under the Sikorski amnesty.

Kārlis Skalders, Under the Sign of the Times: The Story of a Latvian. Rīga: Jumava, 2000

Author was deported to the region of Krasnojarsk from 1941 to 1956.

Juozas Urbšys, La terra strappata: Lithuania 1939-1940, gli anni fatali. Baltica. Viareggio: M. Baroni, 1990

Memoirs of the last minister of Foreign Affairs of independent Lithuania (1896-1991), who in 1940 was arrested by the Soviets and released only in 1954.

Aleksander Wat-Czesław Miłosz. Mon siècle: entretiens avec Czeslaw Milosz. [France]: Editions de Fallois/L'Age d'homme, 1989

Author A. Wat was imprisoned in the Soviet Union in 1940 and then rejoined his wife in exile in Central Asia.

Biographies

Doris Bader Whiteman, Escape Via Siberia: A Jewish Child's Odyssey of Survival. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999

Life story of “Lonek” Jaroslawicz (1929-1995). His family fled Jaroslaw in 1939 and was deported to Russia, then freed under the Sikorski amnesty. They then moved to Tashkent and is mother had to put “Lonek” in an orphanage which was evacuated with the Anders Army (while the rest of the family stayed in Central Asia returning to Poland only after the war ended). Together with almost one-thousand Jewish boys (the so-called “Teheran children”) he stayed in refugee camps in Teheran and Karachi, sailing finally to Palestine in 1943. He stayed there (participating to the first Arab-Israeli War as a member of the Haganah) until 1963, when he emigrated to the United States; his parents joined him in Israel in 1949, after clandestinely emigrating from Poland and living for a while in a displaced person camp in Germany.

Ivan Choma, Josyf Slipyj. Milano: Casa di Matriona, 2001

Cardinal Josef Slipyj (1892-1984), successor of Metropolitan Andrej Sheptysky, was arrested on April 11, 1945 and served 18 years in various prisons and labour camps of the Soviet Union. A chapter of this biography (written by his secretary) is dedicated to Slipyj’s long imprisonment in the Gulag.

Alick Dowling, Janek, a story of survival, Letchworth, Ringpress, 1989

This book is in fact a biography of author’s brother-in-law, Janek Leja (b. 1918). Janek Leja is arrested in January 1940 while trying to cross the border, imprisoned in Przemyśl and then Nikolaev, and sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labor (katorga) in August 1940. He is sent to work to the construction of the Vorkuta-Kotlas railway line in November 1940 and freed under the Polish amnesty in September 1941. He then ends up in Central Asia where we works picking cotton in a collective farm near Nukus, in Karakalpakstan (Uzbek SSR). On March 1942 his group leaves for Kermine; they rejoin the Anders Army and leave Russia on April 1942. He is stationed in Middle East with the Polish Army, then educates himself in wartime London and in postwar years work in South Africa, England and finally Canada until his retirement in 1983.

Alfonsas Eidintas, President of Lithuania: prisoner of the Gulag: a biography of Aleksandras Stulginskis. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistence Research Center of Lithuania, 2001

Aleksandras Stulginskis (1885-1969), speaker of the Lithuanian Costituent Assembly and then president between 1922 and 1926, was deported to Kansk, near Krasnojarsk, in 1941. Only in 1952 he was sentenced to 25 years, but was released in 1954 and returned to Lithuania in 1956 (see chaps. I, XI-XIII).

Masha Gessen, Ester and Ruzya: How My Grandmothers Survived Hitler's War and Stalin's Peace. New York, N.Y.: Dial Press, 2004

This is the story of authoress’ grandmothers, one of which was deported from Bialystok to Bijsk, in Siberia, in June 1941. Freed five months later, she moved to Moscow in 194?

Klaus Hergt, Exiled to Siberia: a Polish child’s WWII journey, Cheboygan (MI), Crescent Lake Pub. 2000

Author tells the story of Henryk “Hank” Birecki, son a Polish gendarme, deported to Siberia in February 1940.

Darcy O'Brien, Dans le secret du Vatican: le récit inédit d'une amitié qui a radicalement changé les relations entre catholiques et juifs. [Saint-Laurent, Québec]: Fides, 1999.

This book is dedicated to the friendship between Jerzy Kluger (b. 1921) and Karol Wojtyla. Kluger’s father (Wilhelm) was a lawyer and a Polish reserve officer; together with his son he escaped to Western Ukraine in 1939 and was deported to the Mari republic in May (?) 1940 (presumably as a bežents). Father and son were amnestied in August 1941 and then joined Anders Army. The son fought at El Alamein and Monte Cassino and married an Irish woman, and after father’s death in London settled in Rome.

Sandra Oancia, Remember: Helen's Story. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises, 1997.

This book is the biography of Helen Najborowski (née Kordas in 1924), who was arrested in Kremenetz on February 10, 1940 and deported to a “labor camp” (more likely a “special settlement”) called Nikolynskya Baza, in Siberia (actually in the region of Sverdlovsk). She was freed under the Polish amnesty and joined a Polish orphanage which was later evacuated to Iran and then India. In 1947 she left India for Britain; there she married in July 1948 and then left for Canada, where she lived in Saskatchewan.

Jaroslav Pelikan, Confessor between East and West: A Portrait of Ukrainian Cardinal Josyf Slipyj. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub, 1989

Cardinal Josef Slipyj (1892-1984), successor of Metropolitan Andrej Sheptysky, was arrested on April 11, 1945 and served 18 years in various prisons and labour camps of the Soviet Union. One (however unsatisfying) chapter of this book is dedicated to Slipyj’s imprisonment in the Gulag.

Natalia Sazonova, Red jazz, ou, La vie extraordinaire du camarade Rosner. Paris: Parangon/L'Aventurine, 2004.

Eddie Rosner (1910-1976), a prominent Jewish jazzman, left Berlin for Poland and then escaped to Soviet Belarus in 1939. Arrested in Lviv in November 1946, he was deported in December 1947 to Chabarovsk; in 1950 obtained to be transferred to the Kolyma. He was freed in the summer of 1954 and stayed in the USSR; he then emigrated in 1972. In 2006 a documentary on Rosner (Le jazzman du Goulag, directed by P.-H. Salfati) has also been realised.

Romans

Rouza Berler, Avec elles au-de là de l’Oural, La Table Ronde, Paris 1967

Novel whose main character, a Polish woman doctor, is arrested on April 13, 1940 and sent to the Northern Kazakhstan, in the district of Koustanaï. The story is likely fictional, but with an autobiographic background.

Andrzej Corvin Románski, Prisoners of the night, The Bobbs-Merrill Company publishers, Indianapolis-New York 1948.

Novel whose main character is a Polish doctor from Warsaw deported to Camp no. 90 in the valley of the River Senya, near the Pechora river, whose prisoners work cutting wood in the Arctic forest. It is fictional but likely based on real characters. It has had also a Spanish translation (Prisoneros de la noche, Caralt 1950). Translated from Polish (by Walter M. Besterman and Blair Taylor) but the Polish edition was published only later (Więźniowie nocy. Londyn: Orbis, 1956).

Zbigniew Domino, Sibériade polonaise. Lausanne: Noir sur blanc, 2005.

Novel on the deportation of Polish military colonists in February 1940. The author, himself a deportee, has been active in the societies of former deportees to Siberia.

Heino Kiik, Marie en Sibérie: roman. [Paris]: Temps actuels, 1992.

Novel on the Estonian peasants from the Avinurme region deported in the southern Siberian region of Zdvinsk (in the Novosibirsk oblast) between 1949 and 1957, based on the experiences of the mother of the author (b. 1927).

William B. Makowski, The Uprooted. Mississauga, Ont: Smart Design, 2002.

Novel (partly autobiographic) whose main character, Janek Tabor, is deported on February 9, 1940 from the village of Zamosze. With his family he is sent to the special settlement Nukhto-Ozyero, in Russia; here he is arrested and further deported to a place near the Afghan border to build a railway. He then escapes, reaching Bukhara – while his family, freed under the Polish amnesty, reaches a collective farm in Uzbekistan. They are later evacuated to Iran separately; he joins the Polish II Corps, one sister ends up in Santa Rosa, Mexico, the other to Nairobi and then joins the Women’s Auxiliary Forces. He finally emigrates to Canada with his girlfriend, another former deportee.

Joseph Stanley Wnukowski, Sun without warmth, London 1966.

Story of a Polish family deported, first to Siberia, then to the North of Archangelsk, then to the goldmines of Gramatuza and the coal mines of Černogorsk.

Pagination

- Previous page ‹‹

- Page 2

- Next page ››