European Memories

of the Gulag

ToPics

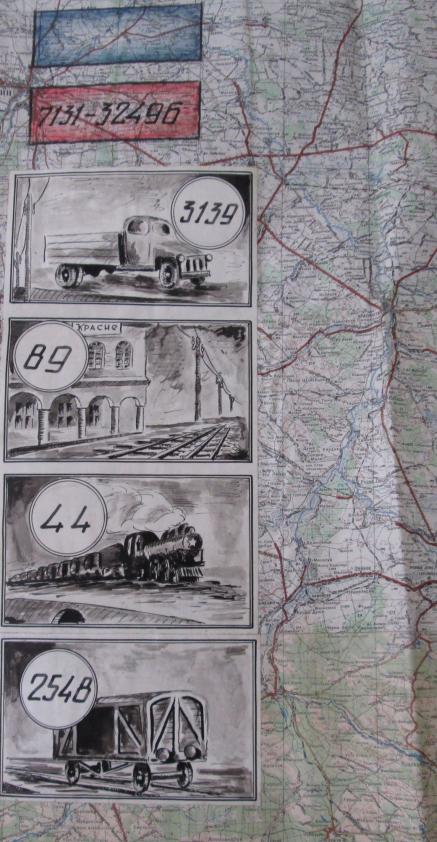

The territories annexed to the USSR, 1944-1952

After the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in February 1943 and the Red Army’s advance west, further deportations were organised.

In the Baltic countries, the people arrested and deported were mainly those who had collaborated with the Nazis, those who had gone to work in Germany, voluntarily or by force, and the partisans from the groups that were fighting against the Red Army. Later, the Soviets launched further waves of deportation, in spring 1948 in Lithuania, then in early 1949 throughout the Baltic countries, targeting farmers who opposed the collectivisation of farmland and often provided the partisans with help.

In Poland, the deportees were the officers and men of the Armia Krajowa (AK), the Polish Home Army resisting German occupation, created in 1942 by the Polish government-in-exile in London, which was active throughout the territories that had belonged to Poland until 1939. During the brief life of the Provisional Government of National Unity formed by the Soviets in 1944, the Soviet political police carried out a number of deportations of members of the national resistance against the Nazis. At the end of 1945, the Polish Ministry of Public Security (MBP) was created and continued these purges.

In Western Ukraine, now part of the Soviet Union, the activists and sympathisers of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) were purged, together with the officers and men of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), collaborators and soldiers of the Galicia Division, a volunteer unit of the Waffen-SS. Thousands of farmers’ families were forcibly resettled in Siberia, because they were seen as the nationalists’ main support.

After 1945, a large number of “ethnic Germans” (Volksdeutsche) living in the territories liberated by the Red Army in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia and the countries that had been German allies, Hungary and Romania, were deported to the USSR.

Hungary and Czechoslovakia also saw the systematic purging of large numbers of individuals who might stand up against the installation of a Communist regime in these countries, and in their borderlands with Ukraine, major forced population movements were undertaken by the Soviets. In Germany and Hungary, the Soviets rounded up young men and women and sent them to labour camps in the USSR to help rebuild the country.

Nadezhda Tutik on her father's deportation (Original in Russian)

Nadezhda Tutik tells the story of her father's deportation from Ukraine, three days after his marriage. Her mother goes to the railway station, and asks the head of the convoy in which her husband is locked up, to leave with him. The convoy leader laughed and told her, "You are a beauty. You'll find a way to remarry. You're not on the list, we're not taking you"...

TIMELINE (1943-1952)

1943

February: Victory at Stalingrad, one of the turning-points in the Second World War.

November: deportation to Central Asia of some 69,000 Karachai from the Caucasus. This was the first collective operation against a “punished people” accused of mass collaboration with the occupier and expelled entirely from their lands. The national autonomy these peoples had was abolished (Karachai autonomous region, Kabardino-Balkar ASSR, Chechen–Ingush ASSR, Kalmyk ASSR).

December: deportation of some 92,000 Kalmyks from the Caucasus to Central Asia.

1944

February: deportation of some 387,000 Chechens, 91,000 Ingush and 37,000 Balkars from the northern Caucasus.

November [*?*]: deportation of some 92,000 Meskhetian Turks, Kurds and Hemshils from Georgia.

May: deportation of some 187,000 Tatars, 22,000 Bulgarians and Armenians from Crimea, 40,000 Greeks from Crimea, Georgia, Armenia and the regions of Krasnodar and Rostov.

30 July: Stalin orders the disarming, arrest and deportation of the officers and men of the Polish Home Army (AK) who had taken part in Operation Burza (tempest).

December: deportation of some 110,000 German-speakers (Volksdeutsche) living in Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.

Winter 1944-June 1945

In Carpathian Ruthenia, arrests are made of members of the Agrarian Party and Hungarian Party, Russian émigrés of the 1920s, Ukrainian and Belarusian nationalists, and Czechs and Slovaks who oppose the territory’s annexation by the USSR.

Spring 1944-1951

Arrest and deportation of hundreds of thousands of real or imagined collaborators, members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), fighters in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), Belarusian partisans, real or imagined Baltic resisters taking up arms against Soviet occupation. The families of the Ukrainian and Baltic resisters the Soviets call “bandits” are deported to resettlement villages in Siberia and the Great North.

1945

January: deportation of some 70,000 Saxons and Swabians (German-speaking Romanians) from southern Transylvania (Romania) to the Donbass, a mining area in the Soviet Union and other Ukrainian industrial areas.

Spring: deportation of some 100,000 people from Slovakia; some are forcibly taken to the USSR, particularly the Donbass, to help in reconstruction; others are sentenced as “war criminals” for fighting with the Germans, Hungarians or Slovaks (Slovakia had taken advantage of Nazi Germany’s domination to declare its independence).

April: within days of the Red Army’s liberation of Czechoslovakia and until February 1948, the NKVD arrests and deports to the USSR the Russian émigrés who had fled the Bolshevik regime in the 1920s and 1930s, mainly members of the cultural and business elite (engineers, lawyers, journalists, writers, translators, officers, teachers, diplomats, business people).

From April 1945: deportation of some 800,000 forced labourers (including 500,000 Germans) from the countries occupied by the Red Army by way of war reparations.

8-9 May 1945: Germany capitulates. The Red Army occupies part of Germany and the Eastern European countries.

Spring-summer: deportation of German-speakers (Volksdeutsche) living in Lithuania.

In Central and Eastern Europe, many people who might hamper the installation of pro-Soviet regimes are arrested and deported to the USSR.

1948

May: as land is collectivised in Lithuania, the NKVD launches Operation Vesna (Russian, “spring”): 40,000 country-dwellers, including 11,000 children, are deported to villages in the Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk and Buryatia regions.

1949

March: mass deportation operation in the Baltic countries, mainly from country areas.

In Lithuania, the operation is codenamed Priboi (Russian, “coastal surf”): nearly 9,000 Lithuanian families, some 30,000 people, are deported to Siberia.

April: similar deportation operation in Moldova.

May: operation to deport Greeks from Georgia.

1951

From June 1949 to August 1952, deportations of varying size are carried out in the Baltic countries. In October 1951, a mass operation, codenamed Osen (Russian, “autumn”) occurs in Lithuania alone, targeting only those farmers who do not join the collective farms. More than 16,000 people, including 5,000 children, are deported to Krasnoyarsk region.

Nadezhda Tutik on her father's deportation (English version)

Nadezhda Tutik tells the story of her father's deportation from Ukraine, three days after his marriage. Her mother goes to the railway station, and asks the head of the convoy in which her husband is locked up, to leave with him. The convoy leader laughed and told her, "You are a beauty. You'll find a way to remarry. You're not on the list, we're not taking you"... raconte la déportation de son père depuis l'Ukraine, trois jours après son mariage. Sa mère va à la station de chemin de fer, et demande au chef de convoi dans lequel est enfermé son mari, de partir avec lui. Le chef de convoi rit et lui dit, "Tu es une beauté. Tu trouveras à te remarier. Tu n'est pas inscrite sur la liste, nous ne te prenons pas"...

Olga Vidlovskaia describes her arrest and deportation.

Olga Vidlovskaia was arrested in 1944 along with her two small children aged eighteen months and four years. She asked the soldier who came to arrest her:

“Why have you come onto our land and are taking us away? And he said, “You’re bastards, Bandera bastards”.

Juliana Zarchi describes her arrest and deportation (Original version in Russian)

Juliana Zarchi was born in Kaunas in 1938 of a Jewish Lithuanian father and German mother. When Lithuania was invaded by the Nazis, her father fled to the East, where he was murdered by the Einsatzgruppen. While only a little girl, she got out of the Kaunas ghetto and managed to survive during the Nazi occupation.

In August 1945, as part of the purges of people of German origin, she was forcibly resettled by the Soviets with her mother to Tajikistan in Central Asia, and only returned in 1962.

Juliana remembers when the Soviet political police arrived at their house in Kaunas and her deportation to Tajikistan.

Juliana remembers arrest and deportation (French version)

Juliana remembers when the Soviet political police arrived at their house in Kaunas and her deportation to Tajikistan.

Juliana Zarchi describes her arrival in Central Asia (Original version - in Russian)

Juliana Zarchi was born in Kaunas in 1938 of a Jewish Lithuanian father and German mother. When Lithuania was invaded by the Nazis, her father fled to the East, where he was murdered by the Einsatzgruppen. While only a little girl, she got out of the Kaunas ghetto and managed to survive during the Nazi occupation.

In August 1945, as part of the purges of people of German origin, she was forcibly resettled by the Soviets with her mother to Tajikistan in Central Asia, and only returned in 1962.

In this extract, Juliana remembers her first impressions on arriving in this foreign land in Central Asia and how the resettlers were sent to pick cotton on the kolkhoz.

Juliana Zarchi remembers her arrival in Central Asia (French version)

Juliana Zarchi was born in Kaunas in 1938 of a Jewish Lithuanian father and German mother. When Lithuania was invaded by the Nazis, her father fled to the East, where he was murdered by the Einsatzgruppen. While only a little girl, she got out of the Kaunas ghetto and managed to survive during the Nazi occupation.

In August 1945, as part of the purges of people of German origin, she was forcibly resettled by the Soviets with her mother to Tajikistan in Central Asia, and only returned in 1962.

In this extract, Juliana remembers her first impressions on arriving in this foreign land in Central Asia and how the resettlers were sent to pick cotton on the kolkhoz.

Olga Vidlovskaia sings ukrainian song

Olga Vidlovskaia sings ukrainian song, in memory of Ukrainians repressed by NKVD.

Нiчь була спокiйна, в селi було цiхо, [The night was calm, the village silent]

Тихим ходом , селом , под’ïзжала машина. [A car drove slowly nearer through the village]

Pозлитiлись кати попiд нашiй хати, [The torturers burst into our houses]

Ареcтують з друж’ю за безцïльну працю. [The arrested our friends to do pointless work.]

Так сидiли друзi пiлтора року, [For a year and a half, our friends were shut up,]

Випустiли дружiв слухати вироку.[They were let out to hear the verdict.]

Вирок прочитали, на смерть засудили, [The verdict was that they were sentenced to death,]

Cxлупотiв скорострiл, дружi похiлились. [As they were shot, our friends trembled.]

Прощай Украïно, прощай рiдна мати, [Goodbye my Ukraine, goodbye my dear mother,]

За безцiльну працю, я дiстал заплату... [For pointless work I got paid.]

The transcription were done by Anastasia Gorelik.

Було всюди тихо

Ні чутки про лихо,

Тихим ходом в село

Заїзжало авто.

Розбіглися кати

По-під наші хати,

Забирають друзів

За підпільну працю.

Кують їх в кайдани,

Вяжуть назад руки

І виводять до тюрми

На вічнії муки.

Їм три рази денно

Води приносили,

А сім раз на день

Нагаями били.

Так сиділи друзі

Більше як півроку,

Випустили друзів

Слухати вироку.

На смерть засудили,

Вирок прочитали,

Злопотіли скоростріли

Друзі повмирали.

Прощай Україно

І ти батьку й мати,

За підпільну працю

Дістаєм ми плату

Не одна жертва

За Вкраїну впала,

Слава Україні!

І Героям слава!

Popular insurgents’ song: Було всюди тихо (There was silence everywhere)

Klara Hartmann describes the end of the war in Hungary and her arrest

“I don’t remember exactly because I was very small: my parents died. And my uncle and his family brought me up. He was a police officer in Gönc. That’s where I lived until I was 14 or so. I went to school. The family got used, or rather, I got used to the family and became fond of them.

The war arrived. And they fled abroad. They fled the war. And they left me in their big flat. So it would not be left empty, they brought a maid in so she would be there and we would stay in the flat.

But the fighting went on a very long time: the Russians withdrew and the Germans came back. It kept changing. My street was lived in by policemen, so to speak, and their barracks was there too. There were many of them who were already retired. The rumour went that the fighting only lasted so long because the police defended the village. But there was surely no one there: everyone was trying to leave. But that’s what people said. And that is why they took me away.

In the end, it was the Romanians who entered the village, not the Germans or the Russians. The Romanians threw their weight around and took away all the people they could.

And then the Romanians, when we were staying in Rakamaz, I think it was… that’s where the train left from. But where they were taking me and why, I didn’t know. I was so young, I was so afraid, I had so many problems that I couldn’t concentrate on anything other than my fear.

How did the arrest go?

There was no arrest! Some soldiers came into the house with someone from the town hall. They took hold of me and took me away.

And they took the maid too?

Yes.

Her as well.

Yes, but I didn’t see her again. I never saw anyone again that I knew from before.”

1944 in Estonia – Eela Lõhmus’s story

In 1944, Eela and her family were caught up in the fighting between the German forces and the Red Army. As they retreated, the Germans advised the local population to evacuate because the Russian soldiers were advancing. Eela and her family and friends fled across rivers and forests under Soviet bombing, between the German tanks.

Orest-Yuri Yarynich describes his arrest (Original version)

Orest-Yuri Yarynich was arrested in December 1949, aged just 15. After a long time in various prisons in the USSR, including the Butyrka in Moscow, he was sentenced to five years’ hard labour for treason and anti-Soviet conspiracy.

Orest-Yuri Yarynich describes his arrest (English version)

Orest-Yuri Yarynich was arrested in December 1949, aged just 15. After a long time in various prisons in the USSR, including the Butyrka in Moscow, he was sentenced to five years’ hard labour for treason and anti-Soviet conspiracy.

A tragic fate

In 1954, Iossif Lipman submitted a long petition to be released from deportation, where he had been sent in March 1949, like so many other Lithuanians in Operation Priboi (Coastal Surf). Before the war, he had been a butcher’s assistant and was probably considered as having escaped deportation in June 1941, when small shopkeepers and artisans were sent away. His letter of complaint, however, is that of a man and his family who, less than 5 years after their liberation from the horrors of German occupation, were deported to Siberia. Iossif Lipman, a Jew from Kaunas, was one of the few survivors of that city’s ghetto, and his letter tells of his tragic fate as he went from ghetto to Siberian exile. The tragic fate of an entire family, because his sons were arrested just after the War (not mentioned in the letter), one for having tried to escape to Poland, as many Soviet Jews did, and the other for knowing of this attempt and not reporting it, and not least for preserving documents concerning the ghetto, which caused the NKVD to accuse him of Zionism.

The accompanying photo shows a number of survivors, including Iossif L. and his wife, just after the liberation of the ghetto, standing in front of the bunker where he had hidden (in the basement of a building in the ghetto).

(see Alain Blum and Emilia Koustova. « L’effacement d’une expérience » [An experience erased], in Emilia Koustova (ed.), Combattre, survivre, témoigner: Expériences soviétiques de la Seconde Guerre mondiale [Fighting, surviving, bearing witness: Soviet experiences of the Second World War], Strasbourg, Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 2020, pp. 273-308).

Petition from Iossif Lipman, dated Krasnoyarsk, 27 July 1954

To the Minister of the Interior of the USSR, Com[rade] Kruglov

Cc: Head of Directorate, Ministry of the Interior, Vilnius

From Cit[izen] Lipman Iossif Naumovich, 84 Lebedev Street, Appt. 1, Krasnoyarsk

Petition

I, Iossif N. Lipman, was born in Kaunas in 1889 and lived there continuously until 1945. Since my childhood, I have specialized in meat, and so I worked from 1920 to 1940 as a manual operator in the Kaunas meat factory.

During the occupation of Lithuania by the German invaders, my family and I were obliged to survive all the horrors of German persecution; on a number of occasions, we were close to dying, and our survival is simply a miracle. We only stayed alive thanks to my two sons who during these years were in contact with the Forward detachment of partisans (headed by Com[rade] Ziman, known as ‘Jurgis’). Unbeknownst to the Germans, they managed to build a safe shelter where we hid during almost the entire occupation, and stayed underground and didn’t go out during the four months before the final defeat of the Germans.

It was only the arrival of the Red Army in Lithuania that saved us; a detachment of sappers dug us out because the Germans, before leaving, had blown up the house above us. That was in July 1944.

When I came out of the shelter, I learnt that all my relatives had been killed, my sisters, my brothers, other relatives, and friends. I could no longer live in Kaunas, nor did I want to, a city full of memories of what happened to us. So I moved with my family to Vilnius.

There I immediately joined the October C ooperative as a butcher, and I worked there until 1948. In 1948, I joined the district cooperative, also as a butcher. I worked there until the unhappy days of March 1949.

In March 1949, I was told, unfairly and unexpectedly, to resettle in Krasnoyarsk.

Throughout my long, hardworking life, I have never owned a house or a shop, and so I was offended by this turn of events just as I was getting old. Wherever I have worked, I have always done the work honestly and conscientiously because it is not in my habit to relate to work any other way.

My eldest son, Lipman Ruben [Ruvim] Iossifovich, born in 1907, was resettled with me because, not being married at that time, he was living with me. Five months later, when we were already in Krasnoyarsk region, we learnt of the sudden death of my wife, who had not stood up to this new shock.

From 1949 to 1951, my son and I worked in the village of Solgon, Uzhur district. Because of our honest work, in 1951 we were sent to exercise our special skills at the Uzhur meat factory, where I received many rewards and bonuses for my work.

In February–March this year, my son, who was living with me, fell seriously ill. Because of the seriousness of his illness, a brain tumour, he was sent to Krasnoyarsk for treatment and stayed in hospital for more than a month; then because there were no brain surgeons in that city, he was sent to Novosibirsk to be operated on. He died during the operation. That was on 12 June 1954.

After this second misfortune for my family, my other children (my younger son and my two daughters) came to stay temporarily with me in Krasnoyarsk so as not to leave me alone, because I have stopped working and depend on my children.

My younger son Lipman Efim [Chaim] Iossifovich, born in 1913, worked as a chief drainage foreman on the building of the Volga–Don Canal until the end of the mission; he received many rewards and bonuses for his excellent supervision of the work, some personally from the Chief of Construction, General Shiktorov, the Minister of the Interior, Com[rade] Kruglov, and his deputy, Com[rade] Serov; you can easily confirm this .

My children only came to Siberia on my account and will have to return home; I hereby request, therefore, that you re-examine my situation and remove the restrictions to which I am subject, for I have no sense of guilt; all our family, to the contrary, has always sympathized with the Soviet government.

I request that you allow me to return freely to my homeland so that I can live as a free man in the few years I have left, and that I no longer bear the burden of being a man with restricted rights, a burden I find intolerable. I request that you authorize me to live where my children live and be able to visit the grave of my late wife.

27 July 1954, [signed] Lipman

Typed letter with handwritten signature of the author, LCVA, R-754 collection, inv. 13, d. 512, pp. 164-165.