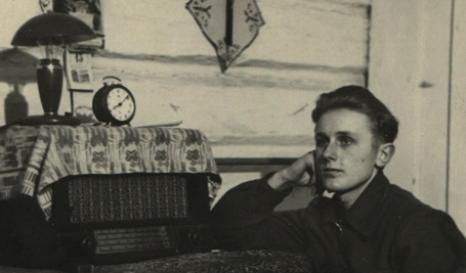

In deportation, the material side of daily life, the world of household objects, was reduced to a minimum. Despite this, or rather because of it, objects took on a special place. They were extremely simple and at the same time precious, rare and present in all the recollections, because they represented memories and links with the world where people were born, the hopes for a better life and the possibility of just surviving. A quilt that saves someone’s life at least twice, first in a frozen railway wagon, then in a Siberian village, where it could be bartered on arrival for a sack of potatoes the family could immediately plant so as to get through the first winter, the hardest of all… A sewing machine, an invaluable resource, so as to help out the neighbours, earn a few roubles (or sacks of wheat), clothe the children or just look pretty, by introducing townsfolk’s’ fashions that had never been seen here before, which female witnesses still remember.

A dress made by a Lithuanian woman was all the more memorable because all the other objects were so poor and rudimentary. In that subsistence economy, suffering not only from the chronic shortages typical of the Soviet economy but also from the virtual absence of money among the kolkhoz workers, paid in kind, the deportees had rapidly to learn how to use plant roots instead of soap, to pick and dry berries to eke out their meagre rations, to make their own tools, kitchen utensils and shoes.

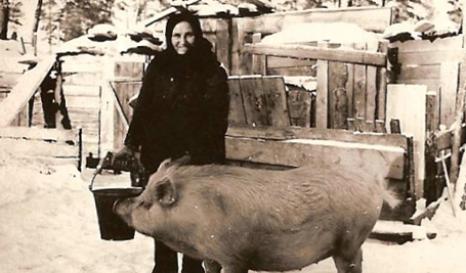

All this left its mark on the minds of the deportees who recount their exile around a few key objects: black skirts patched with white material stand out for Elena Talanina-Paulauskaite as a symbol of the extreme poverty of her neighbours in a village in the Krasnoyarsk region. The presence or appearance of a particular object is also significant, because it could become a source of hope, a promise of survival or a better life, like the pigs that began to be reared in the homes of the Siberian deportees some years after the war. Over and above their practical significance, the pigs reveal an improvement in people’s living conditions, since they had leftovers of food or flour to feed them.

This restricted, tiring daily life became a basis for reconstruction. This was the central element in community life: national attachment was maintained and asserted mainly in daily life (festivals and religious rites, the language spoken at home, national recipes and traditional songs, some articles kept or copied in exile, like Ukrainian or Lithuanian embroidery), but this did not prevent local integration via exchanges of services and shared skills, and also leisure, celebrations and social events shared by the deportees and the locals.

Daily life was an area where different worlds could meet: collective work and private activities, from work in the vegetable gardens to relaxation and celebrations. A meeting of various traditions within the general framework imposed by the ideological, penal and material constraints of the Soviet world, where customs and objects imported from the homeland existed alongside, ignored or encountered the local world.

Emilia Koustova and Jurgita Mačiulytė